By Jennifer Micale

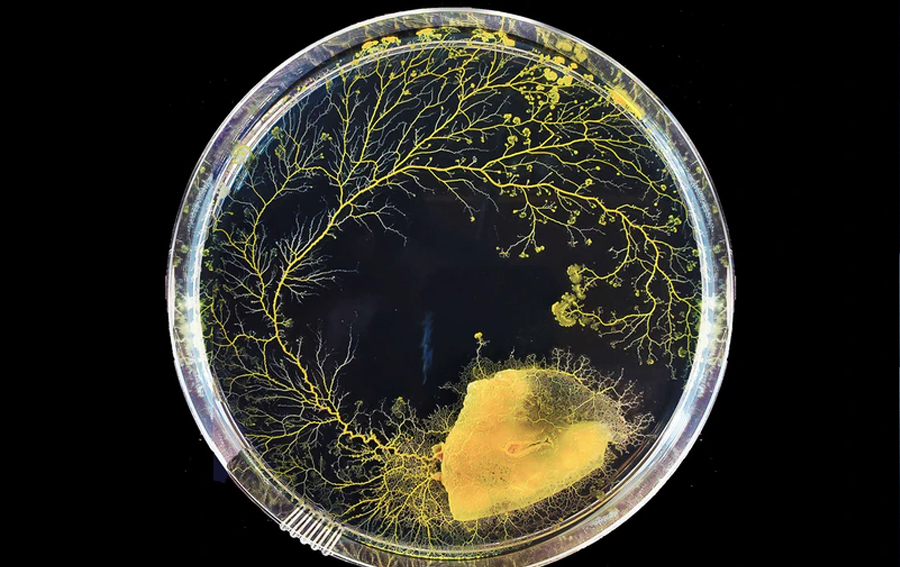

If you didn’t have a brain, could you still figure out where you were and navigate your surroundings? Thanks to new research on slime molds, the answer may be “yes.” Scientists from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University and the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts University have discovered that a brainless slime mold called Physarum polyce

You probably know this story, or a version of it: On Easter Island, the people cut down every tree, perhaps to make fields for agriculture or to erect giant statues to honor their clans. This foolish decision led to a catastrophic collapse, with only a few thousand remaining to witness the first European boats landing on their remote shores in 1722.

But did the demographic collapse at the core of the Easter Island myth really happen? The answer, according to new research by Binghamton University anthropologists Robert DiNapoli and Carl Lipo, is no.

Their research, “Approximate Bayesian Computation of radiocarbon and paleoenvironmental record shows population resilience on Rapa Nui (Easter Island),” was recently published in the journal Nature Communications. Co-authors include Enrico Crema of the University of Cambridge, Timothy Rieth of the International Archaeological Research Institute and Terry Hunt of the University of Arizona.

Easter Island, or Rapa Nui in the native language, has long been a focus of scholarship into questions related to environmental collapse. But to resolve those questions, researchers first need to reconstruct the island’s population levels to ascertain whether such a collapse occurred and, if so, the scale.

“For Rapa Nui, a big part of scholarly and popular discussion about the island has centered around this idea that there was a demographic collapse, and that it’s correlated in time with climate changes and environmental changes,” explained DiNapoli, a postdoctoral research associate in environmental studies and anthropology.

Sometime after it was settled between the 12th to 13th centuries AD, the once-forested island was denuded of trees; most often, scholars point to human-prompted clearing for agriculture and the introduction of invasive species such as rats. These environmental changes, the argument goes, reduced the island’s carrying capacity and led to a demographic decline.

Additionally, around the year 1500, there was a climactic shift in the Southern Oscillation index; that shift led to a dryer climate on Rapa Nui.

“One argument is that changes in the environment had a negative impact. People see that there was a drought and said, ‘Well, the drought caused these changes,’” said Lipo, a professor of anthropology and environmental studies and associate dean of Harpur College. “There are changes. Their population changes and their environment changes; over time, the palm trees were lost and at the end, the climate got drier. But do those changes really explain what we’re seeing in the population data through the radiocarbon dating?”

Reconstructing population changes

Archaeologists have different ways to reconstruct population sizes using proxy measures, such as looking at the different ages of individuals at burial sites or counting ancient house sites. That latter measure can be problematic because it makes assumptions as to the number of people who live in each house, and whether the houses were occupied at the same time, DiNapoli said.

The most common technique, however, uses radiocarbon dating to track the extent of human activity during a moment in time, and extrapolating population changes from that data. But radiocarbon dates can be uncertain, DiNapoli acknowledged.

For the first time, DiNapoli and Lipo have presented a method that is able to both resolve these uncertainties and show how changes in population sizes relate to environmental variables over time.

Standard statistical methods don’t work when it comes to linking the radiocarbon data to environmental and climate changes, and the population shifts connected with them. To do so would involve estimating a “likelihood function,” which is currently difficult to compute. Approximate Bayesian Computation, however, is a form of statistical modeling that doesn’t require a likelihood function, and thus gives researchers a workaround, DiNapoli explained.

Using this technique, the researchers determined that the island experienced steady population growth from its initial settlement until European contact in 1722. After that date, two models show a possible population plateau, while another two models show possible decline.

In short, there is no evidence that the islanders used the now-vanished palm trees for food, a key point of many collapse myths. Current research shows that deforestation was prolonged and didn’t result in catastrophic erosion; the trees were ultimately replaced by gardens mulched with stone that increased agricultural productivity. During times of drought, the people may have relied on freshwater coastal seeps.

Construction of the moai statues, considered by some to be a contributing factor of collapse, actually continued even after European arrival.

In short, the island never had more than a few thousand people prior to European contact, and their numbers were increasing rather than dwindling, their research shows.

“Those resilience strategies were very successful, despite the fact that the climate got drier,” Lipo said. “They are a really good case for resiliency and sustainability.”

Burying the myth

Why, then, does the popular narrative of Easter Island’s collapse persist? It likely has less to do with the ancient Rapa Nui people than ourselves, Lipo explained.

The concept that changes in the environment affect human populations began to take off in the 1960s, Lipo said. Over time, that focus became more intense, as researchers began to consider changes in the environment as a primary driver of cultural shifts and transformations.

But this correlation may derive more from modern concerns with industrialization-driven pollution and climate change, rather than archaeological evidence. Environmental changes, Lipo points out, occur on different time scales and in different magnitudes. How human communities respond to these changes varies.

Take a classic example of the overexploitation of resources: the collapse of the cod fisheries in the American Northeast. While the economies of individual communities may have collapsed, larger harvesting efforts simply switched to the other side of the world.

On an isolated island, however, sustainability is a matter of the community’s very survival and resources tend to be managed conservatively. A misstep in resource management could lead to tangible, catastrophic consequences, such as starvation.

“The consequences of your actions are immediately obvious to you, and everyone else around you,” Lipo said.

Lipo acknowledged that proponents of the Easter Island collapse story tend to see him as a climate-change denier; that’s emphatically not the case. But he cautioned that the ways ancient peoples dealt with climate and environmental changes aren’t necessarily reflective of current global crises and their impact in the modern world. In fact, they may have a good deal to teach us about resilience and sustainability.

“There’s a natural tendency to think that people in the past aren’t as smart as we are and that they somehow made all these mistakes, but it’s really the opposite,” Lipo said. “They produced offspring, and the success that created the present. Even though their technologies might be more simple than ours, there is so much to be learned about the context in which they were able to survive.”

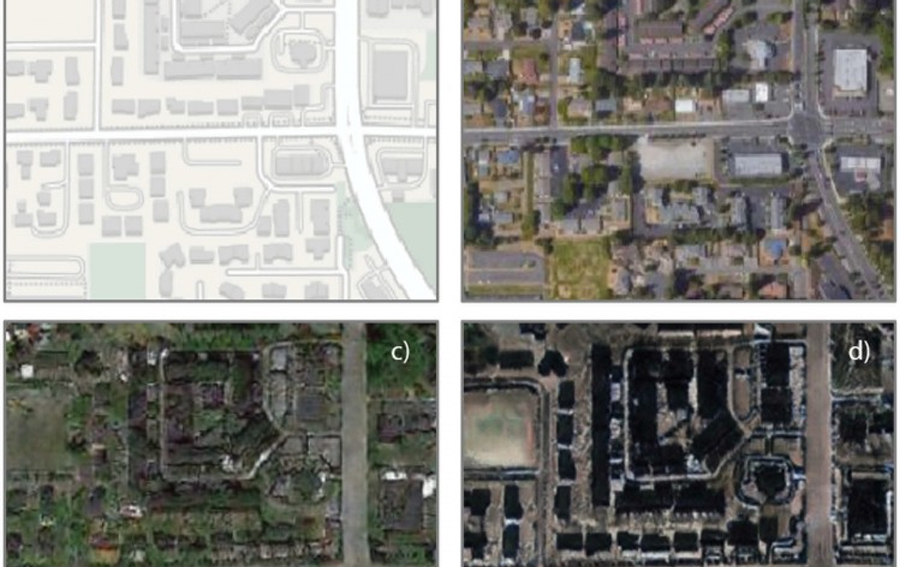

Can you trust the map on your smartphone, or the satellite image on your computer screen?

Can you trust the map on your smartphone, or the satellite image on your computer screen?